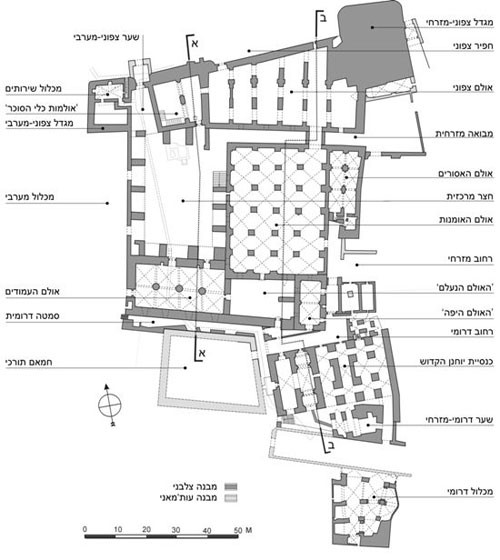

The Crusader structures called the Knights’ Halls or the Citadel of Akko originally served as the Knights Hospitaller Compound. They extend over an area of c. 8,300 square meters.

At the beginning of the 1990’s the structural condition of the Hall of Pillars in the Knights Hospitaller compound became unstable. This became apparent when cracks started to appear in the vaults in the hall and soil and mortar fell from the vault’s core into the hall below.

In the wake of engineering measures that were adopted to save the hall, the Old Acre Development Company decided to go forward with the restoration and development of the underground complex for tourism purposes. This decision resulted in an extensive archaeological excavation, which was conducted from 1992 to 1999 by the Israel Antiquities Authority and financed by the Ministry of Tourism.

Most of the Knights Hospitaller compound was exposed in this excavation. The streets east and south of the compound were also excavated, and an excavation was conducted in the Church of Saint John, which is located just southeast of the compound.

Archeological remains from the Hellenistic Period (300-63 BC), from the Early Arab Period (638-1099 CE), to a large extent from the Crusader Period (1291-1104 CE) and primarily from the 13th century, were uncovered in the compound area. It was in the 13th century that Akko was the capital of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. The destruction of the Crusader structures during the Mamluk Period (1291-1517) left its mark on the compound. During the Late Ottoman Period (1750-1918 CE), the citadel was built as part of the city’s defensive formation on the ruins of the Crusader fortress and during the British Mandate (1918-1948), activists of Jewish Zionist resistance movements were held prisoner there and it served as the main prison in the North of Israel. The archaeological excavation of the Crusader remains and the exposure of a multi-period complex depict Akko’s two golden ages – the thirteenth century and the eighteenth & nineteenth centuries.

The Knights Hospitaller compound is the main monumental testimony to the Crusader Period that was uncovered in Old Akko and to the period during which it was the Kingdom’s capital. Thanks to this exceptional conservational intervention, these monumental remains bear concrete and impressive testimony to the Crusader culture. The compound, parts of which were uncovered and treated in the 50s and 60s, was exposed in all its glory in the 90s.

The state funding allocated to the development of Old Akko in 1993 facilitated the excavation work and the conservation of the compound according to the site’s tourism program. The engineering solutions, documentation and professionalism involved in conserving the structures were an inseparable part of the archaeological activity and the site’s tourist development.

The main challenge in planning the intervention was to find the delicate balance between the conservation and the development requirements in such a way that would protect the heritage components, allow the visiting public to experience the site and understand its significance, and facilitate tourism management on the premises.

The intervention methods were determined based on an investigation of the compound’s components, function, cultural values and state of preservation, as well as on the tourism development requirements involved.

The structures in the Hospitaller compound consist of barrel and cross vaults made of kurkar masonry stones. The compound is primarily Romanesque in style, but it also features Gothic components. Thus the structures of the Hospitaller compound are a combination of components featuring both styles. Thanks to their dimensions, building style, technology and meticulous construction, the Crusader halls offer visitors a moving experience. The massive stone construction, adherence to planning principles and a methodical system of proportions between the various components have created an impressive architecture preserved to this very day.

The most common structural problems recur at varying intensity. The material problems are discernible in the decay of the kurkar stones, the creation of gaps in the stone, salt crystallization on and inside the stone, cracks, erosion of the stone surface, and biological and microbiological patina on the stone. Other problems that are likely to occur are the crumbling of the core mass of the walls and vaults. Structural problems relate to the loss of the bearing capacity of a single stone or structural element, such as a pillar or support, wall or vault deformations that lead to the crumbling of structural elements or the entire structure.

The compound’s structural problems stem from the quality of the building materials, the construction technique, the decay factors of the material and the destructive factors of the structures. Climatic factors such as winds, high humidity, salt crystallization also affect the materials’ resistance and lead to both biological and chemical decay of the stone. The destruction factors affecting the site are many and varied.

The engineering solution to these problems was to create a constructive separation between the Crusader and Ottoman structures. This separation was achieved by stabilizing the Ottoman structure with a system of beams and columns made of concrete and steel.

Of all the halls in the Knights Hospitaller compound, the Hall of Pillars is the one where the most intensive conservational interventions were performed. In this instance, the advanced stage of deterioration caused the structure to crumble. The hall’s remains – which were in a state of acute stone decay – were crushed and cracked and the vault-bearing pillars were disintegrating. In this state, with the loss of the building’s static scheme and in the absence of any immediate and in-depth intervention, the hall’s survival was in jeopardy – a state of affairs that also threatened the stability of the structure above it and those adjacent to it. Thus, the conservational intervention in this case illustrates a broad spectrum of solutions such as minimal conservation, stabilization and preservation, restoration and reconstruction. Thus for example, the conservation of the vaults consisted of cleaning and grouting lime-based mortar into cracks and inner gaps;

in several wall cores, measures were taken to conserve the original material and fill in the missing mortar while other, more recent wall cores were reinforced with debesh fill; the field pillars were restored with modern materials. On the other hand, the constructive function of the end pillars was restored through the use of original technologies. Most of the conservational intervention pertaining to the pillars involved the use of stone and lime-based mortar; in certain places where worn stones were replaced, fiberglass pins were inserted in order to affix the new stones to the original ones. The final processing for the restoration of the stonework was done using Crusader technology in order to achieve an outcome as similar as possible to the original stonework.

The depth of the conservation measures – the stabilization, preservation, restoration and reconstruction with the use of both original and modern technology, as well as the method according to which new infrastructures are installed – is determined based on the state of preservation and the nature of the planned activity on the premises.

The main criterion guiding this intervention was that any stone that does not play a constructive role will be completed or replaced with a new stone matching the original one’s dimensions.

The state of preservation of the Hospitaller compound’s components dictated a variety of intervention levels. Thus, the compound provided ample opportunity to learn about conservation processes and methods. The conservational interventions currently conducted in the compound show how the conservation of this historic monument is professionally handled.

The book entitled “The Knights’ Halls – Conservation of the Hospitaller Compound in Old Acre” is available at the Visitors Center box office.